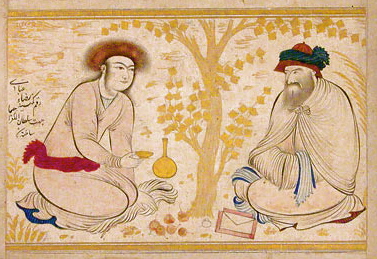

The esoteric wisdom of the Sufis has been preserved in many beautiful teaching stories or parables that can be understood on several different levels. The following is from the book Tales of the Dervishes by contemporary Sufi master Idries Shah.

“Tea” in this story represents a certain kind of direct knowledge, a truth that is at once internal and universal, called irfan in Arabic, and gnosis in Greek. Often in Sufi stories “China” represents the internal worlds, the hidden source of wisdom.

This story is worth reflecting on to see how truth and wisdom are so easily distorted to become exclusive, impractical, hidden, and eventually lost to all but a few.

In ancient times, tea was unknown outside of China. Rumors of its existence had reached other lands, and those who heard of it tried to find out what it was in accordance with their desires

or imagination.

The king of Inja sent an envoy to China, who returned with a gift of tea from the Emperor. But the envoy had seen peasants drink tea, and decided that it was unfit for his royal master; he suspected that the Emperor was trying to deceive them by substituting some lesser substance for the celestial drink.

A philosopher of Anja gathered what information he could find, and determined that tea must be rare, unique and mysterious, for it was known as an herb, a water, green, black, at times bitter, at other times sweet.

In Koshish and Bebinem, people tested every herb and liquid they could find. Many were poisoned; all were disappointed. The tea plant had never been brought to their lands, so no one could find it. Still they continued the search.

The people of Mazhab knew of tea — a small bag of it was carried in their religious processions as a talisman. But no one thought or knew how to taste it.

When a wise man told them to pour boiling water over it, he was hanged as an enemy of their religion, for who else but an enemy would suggest destroying their magic?

Before he died, he told his secret to a few, who then managed to get some tea and drink it secretly. When someone noticed and asked what they were doing, they answered that it was a simple medicine.

A man of understanding spoke to the tea merchants and tea drinkers.

“The one who tastes, knows. The one who tastes not, knows not. Don’t speak of a heavenly beverage; offer it at your banquets and say nothing. Those who like it will ask for more; those who don’t aren’t fit to drink it. Close the shop of debate and mystery. Open the teahouse of experience.”

It was this way throughout the world. Some had seen the tea plant, but did not recognize it; others had tasted tea, but thought it common, certainly not a drink of legend. Still others possessed and worshipped it. Beyond China only a few drank it, and only in secrecy.

Tea was soon carried on every caravan on the Silk Road. Pausing to rest, merchants made tea and offered it to their guests and companions, whether they knew the legends or not. This was how chaikhanas [teahouses] came to be established from Peking to Bukhara and Samarkand.

And those who tasted, knew.

At first only the powerful and those who pretended to possess wisdom sought the ambrosia, then protested, “But this is only dried leaves!” or “Why do you boil water when all I want is the celestial drink?” or yet again, “Prove to me what this is. It looks like mud, not gold!”

When the truth was widespread, and when tea was given to all who would taste, only fools asked such questions. And it is still that way.