“Mountain monks sit playing go.

Over the board is the bamboo’s lucent shade.

No one sees them through the glittering leaves,

But now and then is heard the click of a stone.”

-Po Chu-i, 6th Chinese century poet

The Art of Go

In ancient China it was said that art could be expressed in four essential forms: music and dance, poetry, visual arts, and the game of wei qi.

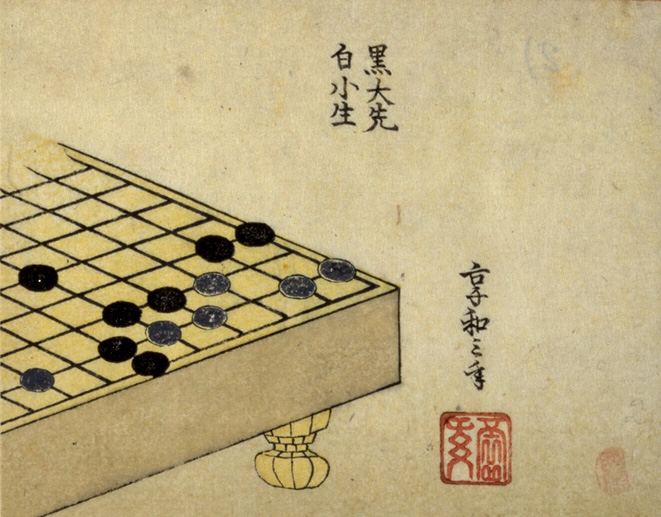

Popularly known by its Japanese name go, weiqi in Chinese which means “surrounding” or “encircling” and describes the strategy of this game. Go is sometimes considered the Eastern version of chess – both being sophisticated battle strategy games.

But rather than a linear battle between two opposing sides as in chess, go is a strategic game to encircle territory in the most elegant way possible, in other words to create space. This resonates very closely with Taoist and Zen teachings of the void nature of all form.

The Philosophy of the Void

“Clay is fired to make a pot.

The pot’s use comes from emptiness.

Windows and doors are cut to make a room.

The room’s use comes form emptiness.

Therefore, Having leads to profit,

Not having leads to use.”

-Tao Te Ching 11

This same philosophy is in the writings of the famous Chinese general Sun Tzu, who incorporated Taoist philosophy of wu wei, “non-action”, into battle strategy:

“The supreme art of war is not to win one hundred victories in one hundred battles, but to subdue the enemy without fighting.”

-Sun Tzu, The Art of War

“The accomplished person is not aggressive.

The good soldier is not hot-tempered.

The best conqueror does not engage the enemy.

The most effective leader takes the lowest place.

This is called the Te [virtue] of not contending.”

-Tao Te Ching 68

Intuition in Battle

In order to win at go there must be a level of intuition, serenity, and the humility to accept the paradox that with any given move one may surround or be surrounded. One must conquer territory without clogging the space to point of uselessness; one must have foresight to look ahead but be present in mind to constantly adapt to the changes brought on by the opponent.

“Know yourself and you will win all battles.”

-Sun Tzu, The Art of War

“Move swift as the Wind and closely-formed as the Wood. Attack like the Fire and be still as the Mountain.”

-Sun Tzu, The Art of War

Enlightenment and Go

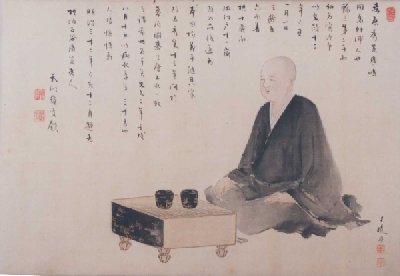

Like Zen practice and the tea ceremony, playing go was officially encouraged as being suitable for the warrior classes, since it imbued the virtues of modesty, patience, and courtesy, as well as clear thought unclouded by the illusion of ego.

Ancient Chinese and Japanese Zen masters associated playing go with the experience of enlightenment, the renunciation of the egoic and materialistic self to incarnate the void nature, as illustrated in the following story.

A monk asks Dongshan (ninth century Chinese Zen master) how to avoid cold or heat, and Dongshan says to go where there is no cold or heat. The problem is to understand where that could be. Dogen begins his explanation by quoting Hongzhi, a Chinese Zen master from the twelfth century, who said: “It is like you and I are playing Go. You do not respond to my move-I’ll swallow you up. Only when you penetrate this will you understand the meaning of Dongshan’s words.”

To clarify Hongzhi’s remark, Dogen (13th century Japanese Zen master) comments:

“Suppose there is a Go game; who are the two players? If you answer that you and I are playing Go, it will be as if you have a handicap of eight stones, and if you have a handicap of eight stones, it will no longer be a game.

What is my meaning? When you respond to my question ‘Who are the two players?’ answer this way: ‘You play Go by yourself; the opponents become one.’ Steadying your mind and turning your body in this way you should examine Hongzhi’s words, ‘You do not respond to my move.’ This means ‘you’ are not yet ‘you’. You should also not neglect the words, ‘I’ll swallow you up.’ Mud within mud. A jewel within a jewel. Illuminate other, illuminate the self.”